|

Stephanie Jones (July 2024) Stephanie Jones (July 2024)

Rating:      of 5 of 5

There are other of Joan's films that

I like her better in, but there

are no other of Joan's 80+ films that I've given 5 stars to

as a whole. This film is stunning: Writing, acting (both stars and

co-players), editing, cinematography---just about every choice here is disturbingly

powerful.

I've seen Baby Jane maybe 8 or 9 times in the past 30 years

(including twice on the big-screen), so it's kind of hard to come

at it from a fresh perspective. But I try:

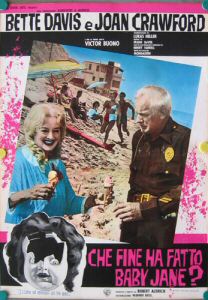

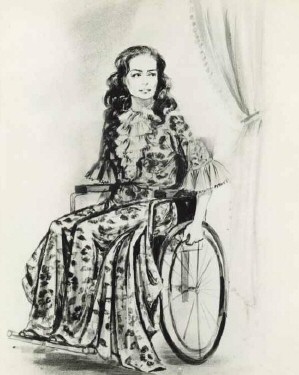

Baby Jane (Bette Davis) and Blanche

(Joan Crawford) Hudson are ageing former-star sisters (one

vaudeville, one movie) who currently

share a Los Angeles home, where Jane is now caretaker for the wheelchair-bound

Blanche. Pre-credits, the first 15 minutes of the film set up the

sisters' psychological

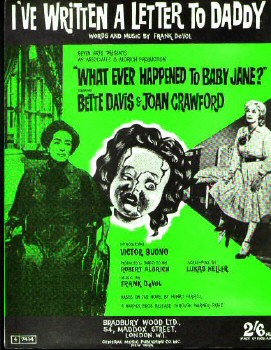

back story: In the first scene, Baby Jane

is a successful, bratty child vaudevillian star circa 1917 who performs

schmaltzy tunes like "I've Written a Letter to Daddy"---with

her daddy introducing and accompanying her. Baby Jane (who even has her own doll

for sale) and her daddy are the stars, and mom and sister Blanche

are the meek onlookers (resentful, in Blanche's case). Cut to 1935:

Blanche has now become the big Hollywood star, who nonetheless still

remains loyal to sister Jane, even getting her movie roles, despite

the mockery of Hollywood directors for Jane's poor screen performances.

(We viewers only see Jane and Blanche here via the actual 1930s

Bette and Joan film clips that the director and assistant

are watching.) At the end of this '30s sequence, the two sisters

(faces unseen) drive up to their house: one at the wheel, one who

gets out to open the gate...we see a hand shift gears, then hear

a crash and shrieks... And then we finally see the film title and credits, with

a "Yesterday" title on the screen...

As the real film

begins: A new neighbor of the Hudson sisters comes home to see scenes

from an old "Blanche Hudson movie" (Joan's actual "Sadie McKee,"

1934) showing

on TV. This now-middle-aged mother has fond memories of the film and

of her early dating life, though the teen daughter (played

woodenly by Bette Davis's real daugher B.D. Hyman, who thankfully

appears only briefly) isn't as impressed.

The daughter casually fills her mother in on the old gossip re the sisters and

the car crash, etc., letting us viewers know that the former scandal still exists

in the present (mirroring the co-existing past-and-present animosity between the sisters).

The decades-long simmering psychological tension

between the Hudson sisters is triggered by these recent

showings of Blanche's movies on TV, along with the accompanying

fan mail and the neighbor's bringing over of flowers to Blanche.

In jealous retaliation, Jane starts playing games with Blanche's

meals: What ever happened to Blanche's bird in the cage that Jane

cleaned? Does Blanche know they have rats in the cellar? It's all

quite harrowing if you haven't seen this film before!

It's not just jealousy, though, that's

contributing to Jane's increasingly erratic behavior. She's also

just found out that Blanche plans to sell their house and find a

"home" for Jane... That's a big part of what makes this

film so interesting: the psychological intricacy of the characters.

Jane is not purely the villain, and Blanche, not purely the poor

victim.

To begin with, Blanche's constant

buzzing when she needs something does become annoying, and you feel a bit for Jane and her

annoyed reactions; and you feel a bit more for her once you

know she knows she's about to be sent to a sanitarium of

whatever sort (AND that Blanche has cut her off from her liquor

supply!). That doesn't excuse Jane's increasingly violent behavior---and

you clearly see that she's losing it---but you can also perhaps

sympathize with her to some extent. For example, near the beginning of

the film, a late-night, drunken Jane starts to melancholically sing

her old child-vaudevillian hit "I've Written

a Letter to Daddy," only to shriek in horror as she sees her

aged face in a too-brightly-lit mirror. In a later scene, though, once she's found

her accompanist, and thus some hope, she does her full "Daddy" number, this

time triumphantly, complete with camera shots from below and footlights,

as if we, the vaudeville audience, were watching and applauding,

as in the olden days.

Joan's Blanche has fewer overtly emotional

dramatic scenes to perform; she's usually called upon to react

to horrible situations---which she does, she does! Aside from

the later drama to come, several of her early quiet line readings especially

stood out to me:

Her first appearance, while watching

her old film on TV: A critical assessment of the director's shot

selection, then a warmly self-satisfied, "It's

still a pretty good picture."

Near the beginning, to maid Elvira,

who comes in looking disgruntled: "Oh,

you've seen Jane."

And later, also to Elvira (rather

ominously): "We're

sisters, Elvira. We know each other very well."

Joan's numerous wordless scenes are

also gripping: The terror on her face when she views the dinner

platters; her gobbling up of chocolates while she's starving; her

simultaneous fear and hopefulness when she tries to throw a note

down to her neighbors, or to contact her doctor before Jane

gets home; her attempts to make it down the stairs despite not being

able to walk.

The ongoing/increasing psychological tension

between the sisters is skillfully (and thankfully!) partially leavened by interludes

with Elvira (Maidie Norman) and Edwin Flagg (Victor Buono), the

pianist who's responded to Baby Jane's want ad.

Elvira is a much-needed voice of reason amid

the neuroses/psychoses of the film, initially pointing out Jane's increasingly

bizarre behavior (hiding Blanche's fan mail, writing dirty words

across her fan photos) and the only person to confront Blanche on

several occasions. She's also a potential savior---the moment after Jane

fires her and Elvira pretends to go home on her bus (yet we see

her still standing behind the bus after it leaves) is a very excitingly

hopeful one. (The entire last hour of this film is incredibly suspenseful.)

Edwin, on the other hand, is the furthest

thing from "reason" (ah, but still a potential savior...). What

a complicatedly weird, well-played character! (Also deserving of

the Best Supporting Actor Oscar that year.) Edwin

lives at home with, and is supported by, his mother Delia. (His relations with his mother

can be summed up after she, with self-righteous horror, tells him of the gossip she's heard re

the Hudson sisters' earlier car scandal and of Jane being found, post-accident, drunk

in

a motel room with an unknown man. Edwin's funnily sneering response

as he storms out: "Well,

wasn't that how I was conceived?") Edwin schlubs

around in PJs during the day, desultorily looking through want ads.

His scenes with Baby Jane are both darkly funny and sad (as is the

movie itself). Once he and Jane meet up for the first time, he tries to impress with

his upper-class British accent (though he's pure Cockney) and tales

of his now-dead father (allegedly a Shakespearean actor in Britain

but reduced to playing menials in Hollywood). Simultaneously, Jane

listens not at all but rather attempts to regale him with tales of her own Daddy... The two

talk past each other, neither listening to what the other is actually

trying to share about themselves. (Shades of Jane's and Blanche's

unsuccessful attempts at communication.)

Bette Davis is a real tour-de-force

in this film: From bitchily irritated sister, to egoist clinging

to past triumphs, to psychopathic tormenter, to little girl crying

for her sister and daddy's help. Her performance is amazing---and

should have won the Oscar that year. Joan's "Blanche" is the

much smoother character here, the most overtly sympathetic, but Bette's emotionally raw

"Jane" is, per the film's title, very much the star of

the show. Such pathos and agony----for her past glories; for her current

trapped and helpless state (though she's not the one in the wheelchair);

for her meager, delusional attempts at a non-existent future.

Rocky

Graziano (December 2014) Rocky

Graziano (December 2014)

Rating:      of 5 of 5

This review will focus on the professionalism and poise Miss Crawford displayed during what must have been an extremely difficult experience working with Bette Davis on "What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?" It is no secret today that these women did not get along, but back when this film was made their rivalry was just speculation. In today's world, actresses would never handle themselves in a manner in which their reputation and the work were put first over ego. Miss Crawford and, to some extent, Miss Davis were able to create a cinematic masterpiece. Much is made of Davis' performance, but Joan shines here in a way she hadn't up until that point. In this film, she is the sympathetic, in many ways pathetic, straight man to Davis' over-the-top power-house role. Joan has to mute herself in order to avoid the wrath of Bette's character, in a way we moviegoers were not accustomed to seeing her onscreen. Joan is in next-to-no makeup and doesn't have any big over-the-top scenes; instead we get a true character onscreen who has tricked herself into believing she is the victim. We follow her on this journey until the truth is revealed in the end.

This is not my favorite film of Joan's; however, as stated in the opening line, I believe the integrity with which she handled this role is important. People love to air their dirty laundry in the modern-day technology

and Facebook era to such an extent that I wonder if strong personalities like those of these two stars would ever put their differences aside to work together on a project that could benefit both of them. I say it day in and day out: we could learn a lot from Joan Crawford, and indeed we did.

Stuart Hoggan (September 2013) Stuart Hoggan (September 2013)

Rating:      of 5 of 5

Even when one overlooks

the legendary real-life animosity between its two leading dames, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? still

retains its glorious hybrid of celebrity psychosis, batshit-hysteria and satire

of Hollywood stardom. Bette Davis illuminates the screen with a no-holds-barred

psychic portrait of child-star- turned-formidable-freak while Joan Crawford makes

for a glamorous punching bag. To cut their feud short, it was Davis who won the

battle by bagging the Oscar nomination for her performance -- but Crawford

satisfactorily won the war by ensuring she would accept the award on behalf of

the eventual winner.

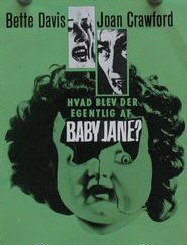

In a tale of grotesque sibling

rivalry, Bette Davis plays Baby Jane Hudson, a popular (and horridly tempered)

vaudevillian child star whose fame fades as she grows older. Joan Crawford plays

her sister, Blanche; overshadowed as a child, she enjoys success as a serious

actress in her adult life. Though Blanche was able to source work for her sister

(in spite of her lack of talent), Baby Jane winds up an embittered and often

volatile alcoholic. This supposed jealousy is the catalyst for a brutal car

accident that leaves Blanche bound to a wheelchair. In their old age, with their

careers a thing of the past, both sisters are confined to a decaying mansion:

Baby Jane as the nurse/prison warden, Blanche as the dependent

invalid/prisoner.

When discovering that her sister intends to sell the

house and potentially have her committed to psychiatric care, Jane's mood swings

develop into cruelty towards Blanche. Between incessant verbal put downs, Jane

cuts Blanche off from the world by withholding her fan mail, then sets on a

campaign of psychological torture. At the height of her mental degeneration,

Jane's delusions of grandeur include an attempt to revive her child act by

enlisting the help of crooked pianist Edwin (a wonderful Victor Buono) while

becoming progressively more violent towards her declining sister.

Robert

Aldrich supposedly invented the rivalry to inject some much needed hype (and

money) into a project that, at first glance, inspired little more than cursory

cynicism. Davis and Crawford were in their 50s, their careers recycled more

times than a spare tire, with the dust long settled on their marquee days. The

“washed up” undertone becomes a frequent thing of mockery, delivered with bitter

irony. It's Davis' Baby Jane who is sent up as the faded novelty act while

Crawford's Blanche is empowered as the once revered actress; early in her career

Davis established her acting chops with a series of acclaimed, and Oscar

nominated, roles while Crawford tirelessly fought to overturn the impression she

was little more than a glamorous mannequin of the movies.

To her credit,

Davis commits to the role of Baby Jane without a modicum of vanity. Beyond the

demented shrieks and venomous drawls, her physical transformation is beyond

ghastly: she adorns chalk-white foundation and a ridiculous blonde ringlet wig,

with a slash of scarlet lipstick on her patented wide mouth. Davis turns Jane

into a crusty, sullen-faced clown whose dialogue fires off with the rapidity and

bite of a machine gun. Later, as the madness unfurls, the clown's infant mind

comes to the core in jolts of panic and genuine fragility. Davis knew she had a

meatier role than her arch-nemesis and she attacked it with all the subtlety of

a sledgehammer. Founded entirely on desperation, her performance is a

success.

Against her usual style, Crawford's interestingly plays her hand

with utmost subtlety. This sets up the festering guilt Blanche contains for

eclipsing her sister's fame, not to mention the ironic finale. Her get-up is

weird, too, with a hairstyle and wardrobe that can be best described as a kabuki

warrior in retire. (Somewhere, a young Faye Dunaway was scribbling down

character notes.) That the film exposes her face in the full throes of weathered

age adds some sincerity to the scene where Blanche's eyes glisten while watching

herself as a young actress on TV. (The clip provided is Sadie McKee;

"It's still a good picture," Blanche poignantly mumbles.) Most of Crawford's

best scenes are private, alone with the fear instilled by Jane's recurring

torture.

Yet there's a plethora of other wonderful things about Baby

Jane away from the two dynamic leads. It’s scored to chilling effect; the

scene where Jane drunkenly loses herself in the memory of stardom and sings

is tragic and fearsome both at once. Then, during an impromptu performance as

Edwin plays the piano, the mansion suddenly converts into a theatre stage with

accompanying footlights. Baby Jane is also peppered with neat and

self-effacing exposition to convey the essential theme of narcissism:

ironically, Bette Davis’s daughter plays a neighbour relishing clips of Crawford

in the period of her cinematic peak; the sheer fact these stars belonged to a

classic Hollywood that was now being sold to TV.

Aldrich has a blast directing

his two leading women, in spite of the perpetual lore of on-set feuding. His

true triumph, however, is how he creatively mines into his material, planting

subversion at the heart of his aesthetic here. Hag horror at its utmost

delicious, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane succeeds on gothic

overtures but offers a more chilling portrayal of the aftermath for stars when

their careers inevitably curdle.

Gabriel

Neilson (August 2010)

As I was reading through the other reviews of this film

[below], I came upon a brief note made by Michael Lia in October of 2009. He wrote, "The rest is history and folklore, but the movie did one thing: It gave Miss Crawford about a million dollars.

Today, I was saying to my mate that I need a "Baby Jane” -- of course

meaning I need a hit, a bang, some good big cash! I need a “Baby Jane”

to come to the rescue!) I am happy it gave Miss Crawford that success

and I will leave it at that."

I tend to agree with this notion, most in the "physical" perspective. (Regarding money, careers, etc.) I did enjoy

the movie. It was, in my opinion, well acted and thought provoking. It

has since become a cult-classic and a bit over-done in some instances.

However, I find it most worth seeing.

Most notable to me, however, is how

this film has become a "gay-cult classic." As we all know both Miss

Davis and Joan to be notable gay-icons (and much much more, of course!)

it is easy to see how this film became that. How many times have we seen

parodies of Baby Jane done by gay men? So much so it's nauseating!

But even so! For myself, this is an important aspect of the film as it

is what led me to find Joan. Being gay opens doors to new things --

without Baby Jane, the door to Joan wouldn't have been opened to me (at

least for now). Thus, this picture does own (however unpretentious)

a fragment in my heart.

So

how do you rate something like that? It transcends that. Not that the

film is one of Crawford's or Davis's best performances. It is not. It is

neither the most emotional. It really isn't much more noteworthy for

much other than that it did star two immortal and powerful actresses.

But for me, it personifies much more. I do think that others like

me hold that in common with this film.

All

in all, a good movie, not great -- but inspirational work done by Joan,

who never left her craft. A woman who lived, breathed, and died for

movie-stardom, her fans, and her love for so many things -- a passion

unlike any other's.

Jack

Boyd

(November 2009)

Rating:

of 5

of 5

I absolutely adore What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? for many reasons.

My mum told me about her favourite film about two years ago. It was called What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? I

coincidentally saw it while I was in a film shop and we bought it, and

watched it that night. From the beginning onwards I was engrossed.

The film actually introduced me to Miss Crawford and Miss Davis,

respectively, and ever since I have loved them both with a passion. But

the film itself is a work of art -- it is definitely one of the most

classic films ever made, as it combines suspense, wit, tension, black

comedy and talent; and it is now my favourite film.

Crawford gives a fantastic performance as the tormented cripple Blanche Hudson, although it seems to be very much underrated. Davis manages to give one of her best performances ever

and steals nearly every scene from the cast. But Joan does overshadow

Davis in quite a few scenes -- for instance, when she drags herself down

the stairs to get help and builds up the tension throughout the whole

of her scene. I couldn't help but sympathise with her, even when we find out

what she really did at the film's climax. I will always remember the

terrifying bird and rat on the supper tray scenes and when Blanche

is violently beaten, as they are terrifically played.

It has been said that there was a feud between the

two ladies while filming this. I don't think there was really a "feud"

on set, though. I think the feud officially took place on the set of Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte, in which Joan was replaced by Olivia De Havilland (another of my favourite actresses), mostly because of Bette's behaviour. I think on the Baby Jane set it was really friendly rivalry.

This is one of the films that should be shown to a Crawford fan, as

it portrays one of her greatest films and performances. I think without

a doubt Bette Davis should have won the Academy Award for Best Actress, and Joan should have been nominated.

Favourite Lines:

Blanche: You wouldn't be able to do these awful things to me if I weren't still in this chair.

Jane: But you are Blanche. You are in that chair!

Blanche: I was watching.

Jane: Then you're an idiot.

Blanche: We're sisters, Elvira. We know each other very well.

Jane (to Blanche): You mean all this time we could have been friends?

Blanche (to Jane): You weren't ugly then. I made you that way.

Jane: Blanche... You aren't ever gonna sell this house. And you aren't ever gonna leave it either.

Jane (to Elvira): I won't and you can't make me. I'm not afraid of you.

Jane: He's going to tell.

Jane: He hates me...

Jane: Blanche. You've got to help me.

Mrs. Bates: That Jane Hudson makes me so mad, I could kill her!

Liza Bates: Gee, that's a good idea. What will we use?

Jane: Oh, Blanche. You know we got rats in the cellar?

Jane: You miserable bitch!

Blanche: It's still a pretty good picture.

Michael

Lia (October 2009) Michael

Lia (October 2009)

Rating:

of 5

of 5

My thirteenth review

for this site -- how fitting!

When I asked my Mom about “Baby Jane” with Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, she let out this tragic, tired sigh and said, “Oh, that was so sad."

I think Miss Crawford thought so, too.

For

my mother, Joan and Bette were still remembered for their past glories

and glamour. My mother was of the opinion that it was a come-down. I

think Miss Crawford thought so, too. Because where did she go from there?

My

partner also despises the movie for some of the same reasons as my mom.

It is a cult classic however, and I am sure that is how I found it -- you

could not miss this movie in San Francisco! Not to mention the parodies of the movie played out on the street or

in the theatres.

I

watched and I loved it, then I watched it again about thirty or forty

more times, and I do not think I like it anymore. The pairing of Joan

and Bette remains the reason for seeing this movie. It ranks and it

reeks at the same time. It suddenly seems like an implausible movie and

it does go on too long. I can actually watch The Spiral Staircase or

The Cat and the Canary with more fright and interest than I do "Baby

Jane." But if you’re a film fan you have to know this movie.

Robert Aldrich

(Autumn Leaves ) directed and hustled this movie deal like a ringmaster.

Oh, if the script were a little better, tightened up a bit, Mr.

Aldrich could have come close to real suspense and cut some of the 132

minutes of film.

Victor Buono

is excellent in his screen debut, and the scenes with "my gal" Marjorie

Bennett and Buono are full of comedic turns and well worth the pairing

(they could have had a series). Bennett also appeared as the waitress in Autumn

Leaves. Aldrich and Joan liked her, too! She was fresh air compared to the

"goings on."

Same for Maidie Norman. She appeared with Joan in Torch

Song as Joan’s secretary. Here she plays her scenes as professionally as Hattie McDaniel would and with as much force and meaning. She is really good and gets my attention. (As a

kid I was sorry she died.) It was still tough being a black actress then, but she hung on!

Bette Davis’s big fat mean boring “Christina”- like daughter is AWFUL, period.

Ann

Barton has a steady history and plays with some interest -- tough luck

she had to play against a piece of wood like Little Davis. Nepotism is

no good this time.

I

can watch Miss Davis and be fascinated. There are moments you feel sad

for this woman, and her acting and characterization are very good.

Madness is creeping in fast. She is a killer. For me, it still has to be a dark night

-- lots of rain and cold -- and then I am ready for some “Baby Jane."

The

rest is history and folklore, but the movie did one thing: It gave Miss

Crawford about a million dollars. (Today, I was saying to my mate that I

need a "Baby Jane” -- of course meaning I need a hit, a bang, some good big

cash! I need a “Baby Jane” to come to the rescue!) I am happy it gave Miss Crawford that success and I will leave it at that.

On a personal note: I was once able to ask an old-time publicist and Warner Brothers’ employee (Frank Casey) about the “feud” with Joan and Bette.

We were in the lobby of the Park Hyatt hotel in Chicago. I was a bellboy, and Mr. Casey had just dropped off Tom Cruise, promoting

Risky Business (he is short). Anyway, Mr.

Casey answered very candidly and said gruffly: “I would pick Crawford

up at the airport and take her to the hotel, and then I would

pick up Davis at the airport and she would just say, “Ohh, you were

with her!” It was all very simple, sarcasm at its best! Like a running joke.

(Mr.

Casey did have a beautiful photograph of he and Miss Crawford from

about 1955 on his entry hall table, signed, of course!)

Logan

Stephens

(March 2009)

Rating:

of 5

of 5

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is definitely a classic motion picture. Stemming from the 1960s horror macabre, Baby Jane is definitely one to give you chill bumps. Unlike modern day horror & thriller films with the blood and gore, Baby Jane is a film that gives you chills without showing anything outrageous. Watching Jane (Bette Davis) go from cruel to Blanche (Joan Crawford) to sweet and subtle to Edwin Flagg (Victor Buono)

is definitely a spine-tingler in itself. You can definitely tell Jane

has mental issues, which you can decipher by watching the film. However, watching Blanche's character is definitely one to get you

sympathetic. You feel for her because, first off, she's crippled and

can't do anything without Jane's assistance, really. Then you see how

Jane mistreats Blanche, and how it progresses to a frightening

stairs-and-telephone-call scene where Jane stands at a hallway door as

Blanche is on the telephone pleading for help. The ending is very

surprising and lets you decide what happens. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is definitely one of

Miss Crawford & Miss Davis' finest works, and as a fan of BOTH actresses, Joan & Bette should have won the Academy Award for Best Actress that year. A fine, fine film and definitely a recommendation to anyone.

Some of the best lines include:

Blanche: You wouldn't be able to do these awful things to me if I weren't still in this chair.

Jane: But you are, Blanche! You are in that chair!

Jane (to Blanche): You mean all this time we could have been friends?

Susan

White (December 2008)

I am 50 years of age ... saw this movie when I was about 7 years old and was

terrified by it. When I was around 30, I invited a friend over to watch it (she never saw it) ... I rented it from Blockbuster ..... from the very

beginning with the 'accident' scene and the music playing ... I had to stop

the movie and apologize to my friend that I couldn't continue watching the

movie because I was already scared.

Very, very good movie!!!!!

Dennis

Jones (June 2008)

I

never miss the opportunity to see this film (and I’ve

seen it several times). The acting, especially by the two principals, comes as

close, to me, as being some of the finest ever on film. Miss Davis’ deranged

character performance proves why she was designated the 2nd best

actress of all time. Miss Crawford plays her part just as well. I simply can’t

imagine any else coming remotely close to what these two achieved with these

roles. And although the film was made in 1962, a lot of people that I know

still discuss this picture, not just for Davis’ or Crawford's performance,

but for the believability these two titans of the silver screen conveyed with

their outstanding performances. We have but very few actors these days that can

match--on a consistent, career basis--the caliber of excellence you’ll

find in these two great performers. If you haven’t seen “Baby Jane”

yet, your “great movie viewing” is incomplete!

Stephi

D. (September 2006)

Rating:

of 5

of 5

Personally, I thought this film was wonderfully made. Of course

everybody's heard about the rivalry between Joan and Bette and it's

exciting to see them work together because you can just kinda sense how

much they hate each other.

Bette Davis

plays a forgotten child star who still lives in the past and Joan plays

a movie star (that must be a hard job for her ) who has become crippled

in an accident that her sister caused. This film has a few thrilling

moments with a surprise ending. I think Bette totally deserved her

Oscar nomination for her role as Jane because she plays a psychopath so

well. Joan does a great job in it as well but she mostly plays her part

for sympathy and gets it.

In one scene when

Joan drags herself downstairs to the telephone to call a doctor to help

her sister, Jane shows up in the doorway to hear Joan saying how

unbalanced she is. When Joan finally sees her she hangs up the phone

and tries to explain, when Jane kicks her in the head. Now I heard that

Bette actually kicked Joan in the head which resulted in two stitches.

Anyway,

I'm not gonna tell you the surprise ending, but I'm just gonna say if

you've longed to see the two great screen queens together then this is

a great film to see.

|

Stephanie Jones (July 2024)

Stephanie Jones (July 2024)

Stuart Hoggan (September 2013)

Stuart Hoggan (September 2013) Michael

Lia (October 2009)

Michael

Lia (October 2009)